[Included in the private papers of D. Creevey, accessed 2019. Written on white A4 paper with black inkjet print in a manilla folder along with similar reports. A handwritten note on the front of the folder reads ‘DOM artefacts files re: WWW – via web access’. The original copy appears to be from a computer, possibly ‘printed‘ from a website, URL unknown.]

ARTEFACTS. FOLDER 382. #2: INTERNET, 20th-c. development, recent innovation. (H.J., jr. unsp.)

[. . . ]

2a. Historical background (see FOLDER 284). Non-magical arithmancy, known in the non-magical community as ‘computer science’, has existed in the west since the 17th century. Based in part off a simplified understanding of Oriental arithmancy (I-Ching), it was advanced by the ‘mathematician’ Gottfried Liebniz in the 1670s and gradually developed as an esoteric interest until the early 20th century, when advances in non-magical technology made practical application of theoretical computing a reality. The first ‘computer’, the Harvard Mark 1 – essentially a building-sized box for performing simple arithmancy – was created by American-based German scientists in 1941. Computers have since advanced at a considerable pace: using a highly simplified form of arithmancy known as binary, they were used throughout the mid-century to execute various tasks previously performed only by magic and thus unavailable to the non-magical community, including advanced astronomy, the launching of explosive projectiles, surveillance, and long-distance communication. As computers advanced in capacity, they decreased in size, gradually shrinking from the size of buildings to that of rooms, then large cabinets, and finally desktop devices. In 1977 three separate American companies released what was known as the ‘trinity’ of ‘personal computers’, portable devices with typewriters (‘keyboards’), visual displays (‘screens’), and significantly increased arithmetic (‘processing’) power. Personal computing became a massive industry in the 1980s and produced remarkable advances in computing technology. Functions previously available only to government organizations and academic facilities could now be accessed in the home by ordinary citizens with no comprehension of computer science (much less true arithmancy).

[. . .]

2b. Summary – computer functions and parts (see FOLDER 289). Computers give the appearance of thinking – and now talking – boxes that solve problems, share information, organize data, and entertain children with crude games. They function by use of binary code, a simplistic arithmetic concept that reduces all possible sources of information to ‘yes-no’ decisions, represented within the computer system (‘code’) as the numerals 0 and 1. The similarities to Gamp’s Law of Transfiguration are notable, and some might theorize that wizard have played a hand in bringing this technology to the non-magical community; however, no historical evidence has been found to support this theory, suggesting therefore that the similarities between Liebniz and Gamp is a matter of coincidence. Though binary code cannot transfigure reality, it can be used to create simulacra of a wide array of human experience. Initially used only to transcribe computing functions and text, it can now reproduce the entire range of audible sound and a passable array of visible imagery. Personal computer can, through screens and audio outputs (‘speakers’), play any recorded sound or, through screens, share any visual medium, including photographs and, in some cases, moving images (‘videos’). Some non-magical thinkers consider this capacity for information-sharing to be the most significant ability of the computer, far exceeding its military or computational potential.

[. . .]

3b. Overview – ‘internet’. The computer’s capacity for information-sharing has significantly accelerated in the past two years due to advances in the binary system known as ‘internet’. Internet evolved out of the fairly simple concept of ‘sharing’ information between computing devices: instead of every device containing its own information and requiring human intervention to pass it through physical means, structures could be added to the computers that would allow them to share the information through binary. Initial internet experiments began in the 1960s and involved an information system known as ‘packets’ that allowed computers to share simple data sets through wires and wave signals, similar to the function of the telephone (see Perkins, 1983). The United States military began using internet as a means of sophisticated weapons/surveillance communication, and by the 1980s many scientific communities began sharing research data through computer networks.

In recent years, internet has shifted from an internal information-sharing system for computer technicians to a potentially global ‘web’ of information-sharing personal computers. This shift comes in large part from the Swiss laboratory CERN and the work of Tim Berners-Lee. Berners-Lee first proposed an internet system that sends binary information in the form of text (‘hypertext’) from a computer (‘host’) to an outside information container (‘server’) which then sends that ‘hypertextual’ information to another computer (‘client’). To make this information transferable and readable, Berners-Lee created a language protocol, ‘HTTP’, and a simple language, ‘HTML’. Information, when shared under these protocols, can easily be transferred from a host computer to a server and then transmitted to a client. Within this language protocol, Berners-Lee introduced the ‘hyperlink’, a word or phrase included in a transmitted text that, when selected on the computer, would produce a new document. Finally, Berners-Lee created a document that, when uploaded to a server, contained a variety of hyperlinks and could function as a starting place for internet users. When accessed on a computer through HTTP, this server ‘hosted’ hyperlinks to all other documents created within Berners-Lee’s internet protocol. An appropriate analogy is perhaps to imagine a parchment scroll containing a library catalogue. Instead of listing the location of each scroll within the library, the researcher taps his wand on the title of a scroll and that scroll suddenly appears before him. Berners-Lee created a visual interface to interact with his internet server which he titled WorldWideWeb. This web initially existed within the computer system of the CERN laboratory, but the access interface could theoretically be added to any comparable home computer and, given the necessary telephone connection, direct that computer to Berners-Lee’s server.

[. . .]

4b. WorldWideWeb. On 6 August 1991, Berners-Lee disseminated the following message to the computer science community:

The WWW project was started to allow high energy physicists to share data, news, and documentation. We are very interested in spreading the web to other areas, and having gateway servers for other data. Collaborators welcome! I’ll post a short summary as a separate article [. . .] The WWW model gets over the frustrating incompatibilities of data format between suppliers and reader by allowing negotiation of format between a smart browser and a smart server. This should provide a basis for extension into multimedia, and allow those who share application standards to make full use of them across the web.

Along with this announcement, Berners-Lee shared the binary information for ‘installing’ the WorldWideWeb interface on personal computers. Computer scientists and hobbyists around the world have begun to experiment with accessing the server and, more importantly, creating their own material using the HTML language and HTTP protocol.

[. . .]

5a. Current capabilities – summary. At the time of writing (July 1992), the capacity of the internet as an information system is difficult to assess. As Berners-Lee notes in his initial announcement, the ambition of many internet users is to create a tool for sharing ‘multimedia’ – in other words, visual representations, moving pictures, sound, and perhaps immersive sensory experiences – through telephone wires and waves. So far, the internet has primarily been used as a means to communicate text. An advanced form of post, sometimes refereed to as ‘electronic mail’, is perhaps the most used function of internet. Up until the present, the only non-text media has been crude images created by binary pixels to aid in internet navigation; internet users refer to these as ‘graphical interfaces’, of which their are currently two (Erwise, created in Finland, and ViolaWWW, created in California).

[. . .]

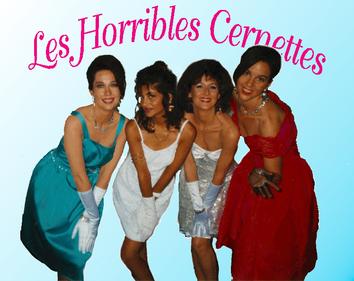

5d. Current capabilities – visual transmissions. On 19.7.92, a CERN employee, presumably Berners-Lee, shared what appears to be a pixelated photograph, enhanced by computer visual editing, over internet (appendix C). The photograph, depicting four women in celebratory attire underneath the words ‘Les Horribles Cernettes’, is stationary and of a somewhat grainy quality, but nevertheless appears to demonstrate internet’s ability to share complex images through servers. As such it now imitates the magical community’s ability to send two-dimensional images by means of the Protean Charm, albeit at a significant lower quality and speed.

[. . .]

Recommendations:

1. Investigation into the nature of image sharing and potential pursuit of arithmetic strategies for transferring visual information as a supplement to – and potential replacement for – to the Protean Charm.

2. Training in HTML coding and staff-wide fluency on the nature of binary arithmancy.

3. Continued close surveillance of CERN laboratory, as well as enhanced surveillance of University of Minnesota, University of California XCF, and Helsinki University of Technology (see coordinates, Appendix D).

4. Continuation of media strategy under Protocol Q.